Several years ago, new versions of Mac OS X were a very big deal because they only happened every 18 to 24 months. Each year, John Siracusa would write no less than a book about the system, and there would be endless discussion about the merits and the disadvantages of the new software version. In the early days, Mac OS X releases were universally faster and better in nearly every way than their predecessors.

Starting at about 10.7, Apple started releasing much more frequently and adding functionality that seemed to deeply offend many Mac users. To this day, many people specifically seek out Macs from 2011 and earlier that can run 10.6.8, in order to avoid completely optional functionality such as Launchpad and a native full-screen view.

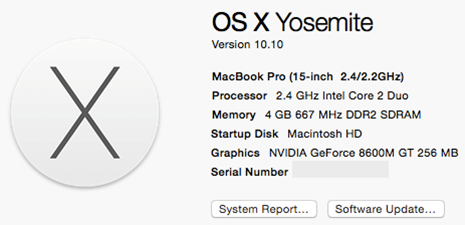

Mac OS X 10.8 after that was the first time since the launch of the Intel-based Macintoshes that some of the oldest and lowest-end Intel based Macintoshes were excluded from the latest release. Mac OS X 10.9 and 10.10, however, do not change the requirements from 10.8. Most of the systems that do not run the latest Mac OS X are from the early transition phase of Apple's Intel-based hardware, and the systems that got eliminated are based on the positively ancient 945 chipset or do not support 64-bit EFI, along with a few systems that have weak integrated graphics components.

However, a common comment about older systems (such as the late 2007 MacBook Pro) is that they're too slow to efficiently run the new operating system. I question this notion. In fact, I question it so much, I took a late 2007 MacBook Pro we had laying about at work, and upgraded it directly from a relatively unused (i.e. "peak performance") install of Mac OS X 10.6.8 and upgraded it directly to the customer preview of 10.10.

Most of the people making these comments don't' qualify them with information about what tasks they're performing, but from the perspective of a general purpose Web-access and document processing computer, I've been using such a 2007 MacBook Pro with Mac OS X 10.10 Mavericks for a few weeks now. Although I could probably put Final Cut Studio on this machine and handily edit 1080p video (just as well as Final Cut Studio 2 could in 2007 when this system was new) I'm not bothering because if that was your task for this system when you got it new, you've probably replaced the system with a faster one now.

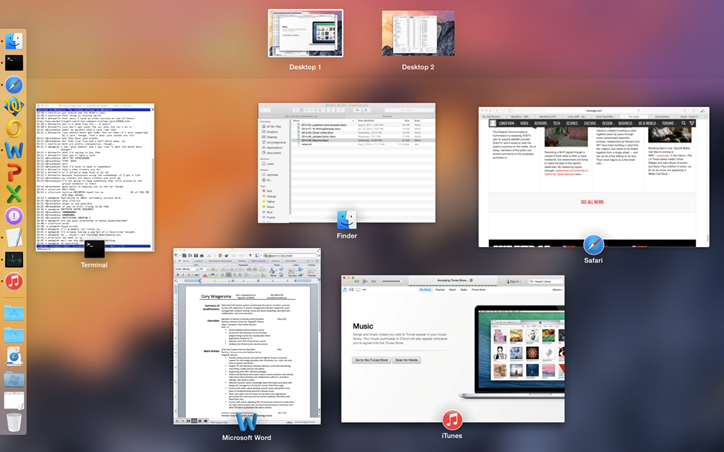

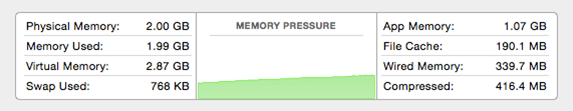

Memory Compression was introduced in Mac OS X 10.9 and was hailed as the thing that was going to make two-gig MacBook Air more usable. To take a look at this, I pulled half of the memory out of this system. It's worth noting that this system still has a spinning disk, faster processor, and a discrete graphics processor, so the performance isn't going to be exactly the same as a real MacBook Air. Despite this, I feel like the system held up fairly well. I really like the visual representation of "memory pressure" in Mac OS X 10.9 and 10.10 and just based on my experiences with 10.9, I feel like the algorithm for memory compression has improved. Over time as I used the system fairly hard, I noticed that more of the memory reached compressed status.

With just two gigs of memory, though, the system was very different to use. With four gigs of memory, I was able to use the system without worrying about the performance aspects of running, say: Word, iTunes, Safari (many tabs), Terminal, and Excel all at once. With two gigs of memory installed, it was really clear that the system was only usable for one or two tasks at once, or that you were going to be waiting for tasks to switch in and out, or for compression to take effect. On a MacBook Air with a solid state disk, this process would be a lot faster, but because the graphics memory is shared on most MacBook Airs, you have that much less usable physical memory to begin with.

Mac OS X has always been this way, but it's great to see that the system is using as much of the memory as possible for things like a file cache. Mac OS 9 and Windows XP would simply let this memory sit idle, even though it saves battery life and improves the overall performance of the system to use the resources this way.

Other things about Mac OS X 10.10 are nice, and/or I've simply grown used to them. For example, in the process of upgrading through the public betas, the icons have changed and some of the applications that still had their rich Corinthian leather skins on have gained the new simpler and flatter appearance.

The new functionality of Mac OS X, not all of which runs on the oldest hardware, is also pretty nice. For example, the newest Macs can take phone calls on your iPhone over Wi-Fi. (Although, it turns out, iPhones on T-Mobile can now do Wi-Fi calling on their own.) The oldest Macs have long "missed out" on functionality like this, and although it's a bummer that some features of the new operating system don't run, I don't personally consider it a huge loss.

Of course, it's well known that I'm a fairly big advocate of running an operating system that gets patches, and if possible, the newest operating system. Given that Apple will be giving this thing away for free, I will absolutely be upgrading my own Mac, even if not on the first day. I may eventually install Final Cut Studio on this system, just because I have the software and this machine is capable of it. That would simply be to prove a point, and not because it's actually helpful or interesting to showcase it.

It depends on your workload, of course, but if this is what Mac OS X 10.10 is to be like on the slowest hardware that can run it, then owners of Macs up to seven years old are going to be in for a treat. In addition to be every bit as fast at everyday tasks as 10.6.8, it builds on 10.9's improvement of power management and memory handling, and the entire operating system is sprinkled with neat changes and the visual look of the system has been simplified and re-unified with that of iOS. The new visual styling is great. When you're using Apple's own built-in applications such as Notes, iCal and Reminders, it feels a little bit less like a trip into somebody's self-decorated game room basement and a little bit more like you're using a computer. Faux leather and pixel metal are out and it's great.